Drug lord Pablo Escobar was killed 25 years ago, ending the life of one of the world’s most notorious outlaws, responsible for an unprecedented number of deaths and a bomb attack in Colombia.

But overcoming Escobar’s legacy is not easy and in his hometown of Medellin, residents who live in homes he built for them are planning heartfelt tributes to mark Sunday’s anniversary.

“He was a good person who also had to do bad things, otherwise he would have been killed earlier. He helped many,” Emanuel Lara Rodriguez, a Mexican tourist in Colombia told Al Jazeera.

Escobar was killed in a rooftop shoot-out with police and army soldiers in Medellin on December 2, 1993, one day after his 44th birthday and five months after he appeared on Forbes magazine’s list of the world’s richest people for the seventh time.

The mansion where Escobar lived with his family was bombed in 1988 and abandoned, but today it has become a symbol of Escobar’s era – one the authorities want to get rid of.

The home has become a top tourist attraction in Medellin’s El Poblado neighbourhood. But it will soon be replaced with a public park that will be dedicated to the thousands of people killed in Colombia by drug gang disputes.

“It’s a tribute to the victims and all the people that defended legality,” Daniel Vasquez, collaborator at Colombia’s Memory House Museum, told Al Jazeera.

“We have moved forward but we still have huge challenges because the violence and drug trafficking are still here.

“They’ve changed and are less intense but we need to keep working on our culture so that it will always be less present,” he added.

The park will cost an estimated $2.5m. Renovating and reinforcing the mansion would have cost $11m, according to the city.

|

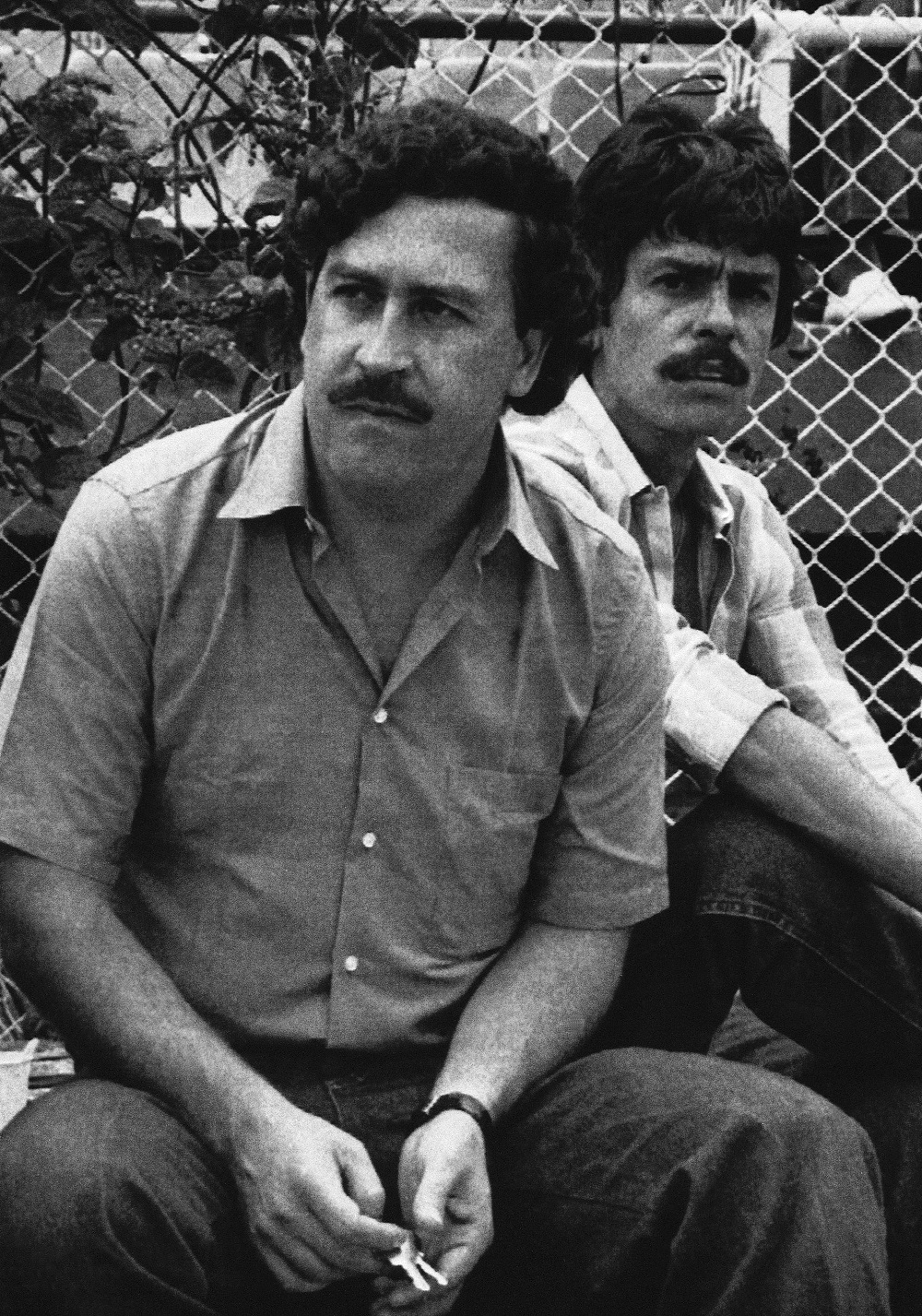

| A televised offer by the Colombian government for drug kingpin Escobar, right, and Gonzalo Rodriguez Gacha [File: John Hopper/AP Photo] |

Complicated legacy

Twenty-five years ago, Medellin, Colombia’s second-largest city, was infested with drug violence, car bombs and regular shootouts, as drug gangs, state forces and private militias fought for supremacy.

In 1991, at the height of Escobar’s conflict with authorities, Medellin had recorded 6,349 murders.

But the fascination with the legend of Escobar has overshadowed this reality for many, and stories around him are still popular.

In Antioquia, an area surrounded by drugs, many still speak about the fact that it has the biggest concentration of hippopotamus outside of Africa – animals that, having escaped from Escobar’s ranch, were left to roam wild instead of being transferred to the zoo, according to reports from El Pais.

According to Netflix, more than 60 million viewers have been attracted to the eccentric details of his life through hugely successful series such as Narcos and other TV series and documentaries.

And for many, he is still the “Colombian Robin Hood”, particularly in the neighbourhood that bears his name, where he donated 443 houses to people who earlier lived at the local dump.

“I see him like a second God,” resident Maria Eugenia Castano, 44, told AFP news agency, as she lights a candle at an altar that bears Escobar’s photograph. “To me, God is first, and then him.”

But the damage he inflicted is also remembered. Escobar’s victims are still seeking justice and a balanced narrative of what really happened.

“Pablo will confuse you,” Yamile Zapata a stylist in Medellin said.

“If you want to look at the good side, he was very good. If you want to look at the bad, he was very bad.”

|

| The Colombian military in the Hacienda Napoles, a sumptuous estate belonging to the Medellin cartel leader Escobar [File: Getty Images] |

SOURCE:

Al Jazeera and news agencies