Colombo, Sri Lanka – Sri Lankans have voted to elect a new president in an election that has seen rising religious tensions and a slowing economy take centre stage.

Gotabaya Rajapaksa, a former defence minister and brother of two-time former president Mahinda Rajapaksa, and Sajith Premadasa, the ruling United National Party’s (UNP) candidate, are the top two contenders in a poll that has a record 35 candidates vying to lead Sri Lanka‘s government.

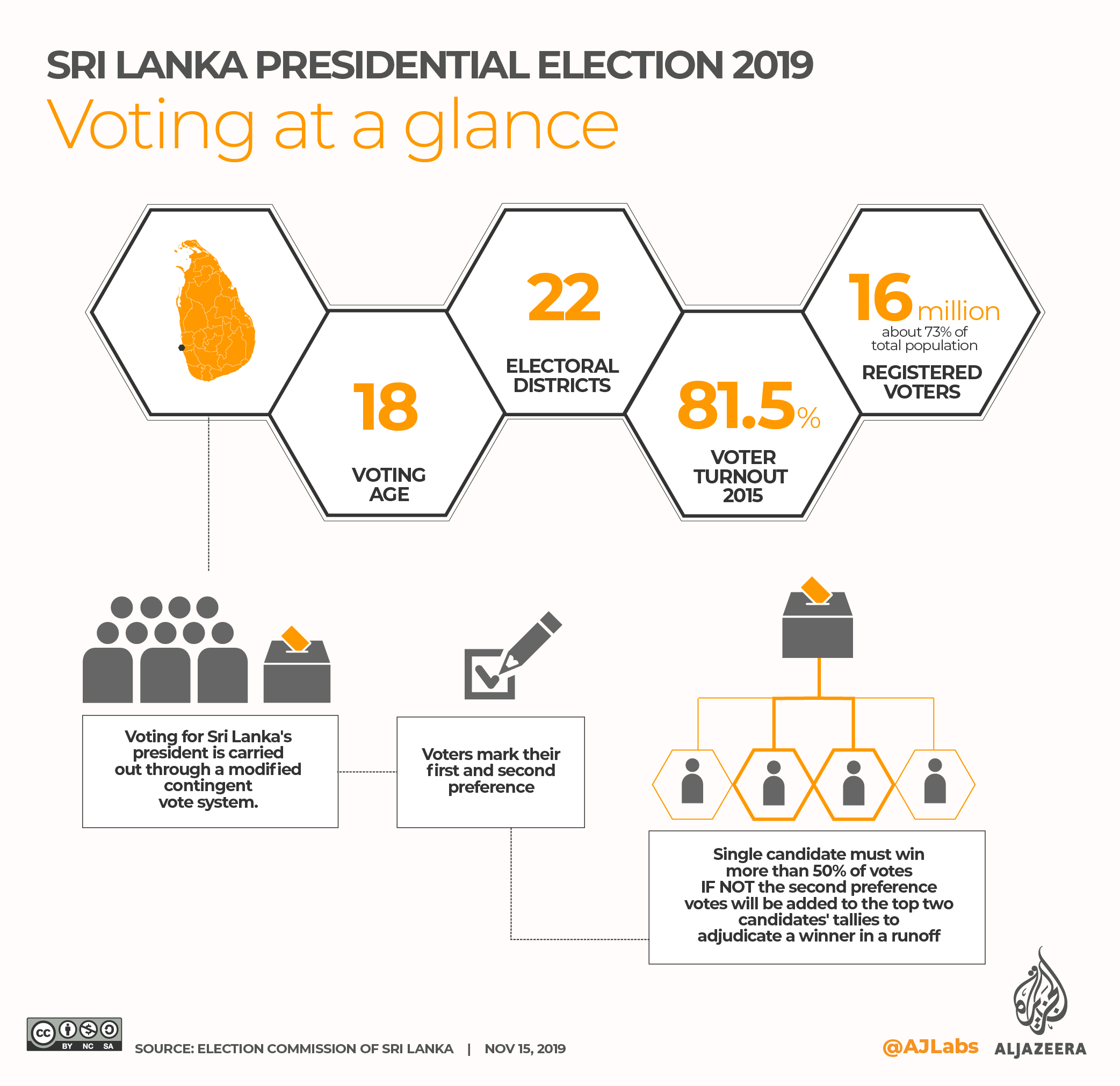

Polls opened at 7:00am local time (01:30 GMT) on Saturday and closed at 5:00pm (11:30 GMT). Some 15.9 million Sri Lankans were eligible to vote at 12,845 polling stations in the country’s 22 electoral districts, according to the Election Commission. Final results are expected by Sunday.

More:

As of midday, election observers reported sporadic cases of limited violence and electoral violations, including two cases of assault and 41 of intimidation.

Early on Saturday, unidentified gunmen opened fire on a convoy of more than a 100 buses carrying voters – mainly Muslims – at Thanthirimale, about 240km (150 miles) north of Colombo, election observers said.

“Unidentified groups shot at and pelted stones at the buses,” said Manjula Gajanayake, the national coordinator for the Colombo-based Centre for Monitoring Election Violence (CMEV).

At a press conference later on Saturday, police spokesperson Nuwan Gunasekara said there were no casualties in the attack, which damaged three buses. He added that no arrests were made but local police had opened an investigation.

In all, the spokesperson said 26 people were arrested across the country on Saturday; eight for taking pictures with mobile phones inside polling stations and 18 for other electoral law violations.

Divisive campaign

Historically, voter turnout for presidential elections has been high, with more than 81.5 percent of voters casting their ballots in the last election in 2015.

Outgoing President Maithripala Sirisena, who won that vote, will not be seeking re-election, but his Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) is backing Rajapaksa.

Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, who Sirisena unsuccessfully attempted to remove in October last year, is backing his own party’s candidate, Premadasa.

The six-week campaign divided the country, with Rajapaksa promising to bring in strong, centralised leadership to tackle security, boasting of his credentials of being the defence minister who presided over the end of Sri Lanka’s 26-year war with Tamil rebels.

Rights group have long called for accountability for allegations of enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings and other violations allegedly committed during that tenure.

According to a United Nations report, as many as 40,000 Tamils may have been killed in the final months of the war.

Mahinda Rajapaksa, who Gotabaya says he will name prime minister if he is elected, has also been accusedof widespread rights abuses aimed at silencing dissent during his previous two terms in power.

Voices at polling stations

Voters formed orderly lines outside polling stations across Colombo as voting opened on Saturday.

Leslie Rajakaruna, 78, a retired railways officer, said he was voting for Gotabaya Rajapaksa because he was “a strong leader”.

“There is too much foreign involvement, Sri Lanka should control itself,” he said, alleging interference in the country’s domestic policies by “the United States, European countries and the United Nations”.

Rajakaruna dismissed allegations of war crimes against the Rajapaksa’s as being politically motivated.

“They will not be able to prove a single abduction, it’s all fake,” he said.

Poulasingham Sridarasingh, 67, a Tamil bookstore owner, said he was voting but did not hold any expectations for things to get better for his ethnic community.

“We have a right to vote, but we [Tamil people] are not getting anything out of it,” he said.

Sandya Kumari, 59, a cleaner in Colombo’s Wellawatte area, said she was voting for the UNP’s Sajith Premadasa because “he thinks about poor people”.

Premadasa’s campaign has focused on lower income groups, promising government-subsidised housing, more jobs and other benefits.

Pathinagodage Rajith, a mason, said he was voting for Gotabaya Rajapaksa because he believed in his economic programme.

“Economic issues are our biggest concern. Whatever we earn we have to spend,” said the 57-year-old, who earns roughly 30,000 Sri Lankan rupees ($166) a month.

Imran Muhammad Ali, 38, works in the IT sector, and said he was voting against Gotabaya Rajapaksa because of the allegations of rights violations during his brother’s term in office.

For voters, the election comes as economic growth is slated to slow to 2.7 percent this year, according to the IMF, and security has become a major issue following the Easter Sunday suicide attacks that killed at least 269 people.

“The cost of living and the state of the economy, these are our biggest issues,” said Shriyani Gamage, 56, a homemaker in capital Colombo. “We don’t have enough money … this country has gone to the dogs.”

Analysts say there is little to choose between the candidates’ economic policies.

“It’s a form of crude mercantilism where the rich in Colombo can prosper but the middle class will also feel squeezed out,” said Kumaradivel Guruparan, an academic in the northern city of Jaffna. “It is crude capitalism that is then sprinkled with here-and-there policies inspired by welfare economics or socialism.”

Mounting tensions

The six-week campaign in a neck-and-neck race has seen tensions mount across Sri Lanka, with the Centre for Monitoring Election Violence (CMEV) documenting at least 743 electoral violations, including at least 45 cases of assaults or threats.

The alleged violations are split relatively equally between the two leading parties, Rajapaksa’s Sri Lanka People’s Front (SLPP) and Premadasa’s UNP, the CMEV data shows.

Election observers say there has been widespread misuse of government resources in the run-up to the poll, with state governors, local government officials and others all using state resources to illegally back both candidates.

“I am not willing to say this election is free and fair,” said Gajanayake, CMEV’s national coordinator. “Due to these [violations], elections can be manipulated.”

Gajayanake pointed in particular to the backing of Gotabaya Rajapaksa by prominent Buddhist religious leaders, who have allowed his party to campaign on temple premises.

Sinhalese – who are mainly Buddhists – form about 70 percent of Sri Lanka’s 21.8 million citizens, according to the Sri Lankan government data.

Tamils form roughly 15 percent of the population, with Muslims – many of whom consider themselves a distinct ethnic group – forming roughly 10 percent.

Analysts say the minority vote will be crucial in determining who wins the election.

“Both Tamils and Muslims are likely to vote overwhelmingly for Sajith Premadasa, although not necessarily because of his policies,” said Ahilan Kadirgamar, a Jaffna-based political economist, citing fears among minority communities of repression under a Rajapaksa government.

On Wednesday, the International Crisis Group (ICG) said the prospect of a Gotabaya Rajapaksa win had created “fear of a return to [a] violent past”.

“The prospect of a new Rajapaksa presidency has heightened ethnic tensions and raised fears among minorities and democratic activists,” wrote ICG Sri Lanka director Alan Keenan.

“They worry electing Gotabaya, a strong Sinhala nationalist, would deepen already serious divides among the country’s ethnic communities and threaten its recent modest democratic gains.”

Constitutional crisis: Round two?

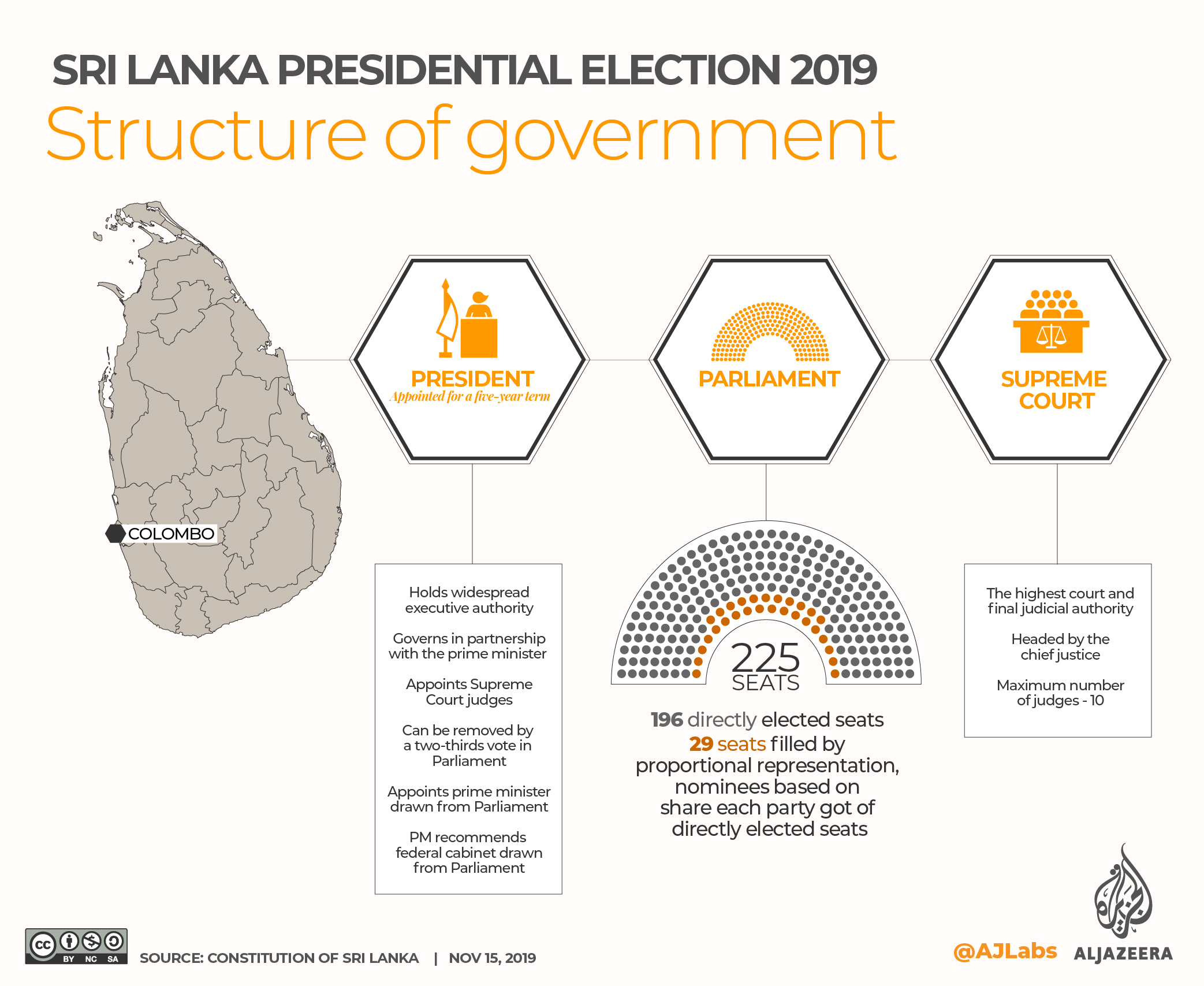

Analysts say Saturday’s vote can also be seen as a continuation of last year’s constitutional crisis, when Sirisena attempted to replace Wickremesinghe with Mahinda Rajapaksa, but was ultimately forced to reverse his decision after the Supreme Court said he did not have the power to dismiss the prime minister.

With both top candidates having stated their intention to replace Wickremesinghe if elected, the possibility of a standoff immediately following the vote is strong, said Kadirgamar.

“Once the presidential elections are over and the president is elected, there will very quickly be a reconfiguration of forces in parliament,” he said.

If Rajapaksa wins, analysts told Al Jazeera he is likely to attempt a vote of no-confidence against Wickremesinghe in parliament. If Premadasa wins, he may ask Wickremesinghe – his party’s leader – to step down, they said.

“You’ll have an awkward cohabitation, either a temporary one if Gotabaya Rajapaksa wins, and a possibly more long-lasting one under Sajith Premadasa,” the ICG’s Keenan told Al Jazeera.

The potential political ramifications are complicated by recent changes to Sri Lanka’s constitution that weaken the power of the presidency and will become effective for the first time following this vote.

“Previously everyone knew and assumed that the new president would set up his own administration, his own cabinet and appoint his own prime minister,” says Asanga Welikala, a Sri Lankan constitutional expert. “That is no longer a power that the president has.”

Under the 19th amendment to the constitution, the presidency has been stripped of key powers, including eligibility to hold ministerial portfolios, from this election onwards.

Sri Lanka operates a semi-presidential system of government, where the executive comprises of the president, who is directly elected, and a prime minister and cabinet which are drawn from and answerable to parliament. It is “a system built on tension”, according to Welikala.

“It is essentially a hybrid system between the US presidentialism and the UK parliament system,” he said.

“The president is head of state, head of cabinet and head of government. He is the only person who is directly elected. The president does have power, but it is not untrammelled power [anymore].”