Warfare was uncommon among hunter-gatherers, and killings among nomadic groups were often due to competition for women or interpersonal disputes, researchers in Finland said Thursday.

Their study in the U.S. journal Science suggests that the origins of war were not — as some have argued — rooted in roving hunter-gather groups but rather in cultures that held land and livestock and knew how to farm for food.

For clues on what life was like before colonial powers, missionaries and traders entered the scene, anthropologists examined a subset of records from a well-known database that contains information on 186 cultures around the world.

Douglas Fry and Patrik Soderberg of Abo Akademi University in Vasa, Finland, chose to examine only the earliest existing records on those that had no horses and no permanent settlements, leaving them with 21 mobile foraging societies for analysis.

“To be purists, we took only the oldest high-quality sources for each culture,” Fry told the journal Science, adding that these studies would best showcase the people’s traditional ways.

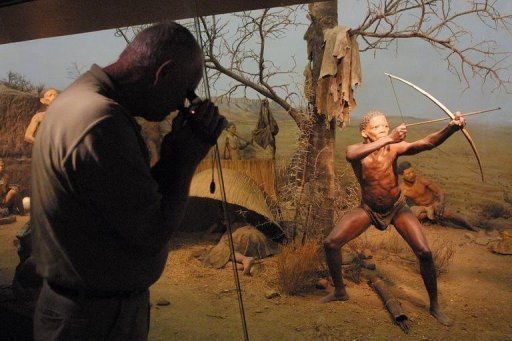

The groups included the Montagnais people of Canada, the Andamanese people of India, the Botocudos of Brazil, and the !Kung people who live in isolated areas of Botswana, Angola and Namibia.

These old records contained data on 148 lethal events. Of the 138 killings in which circumstances were “unambigious,” 55 percent were determined to have involved one killer and one victim, the study said.

In most killings (85 percent of the time), the killer and victim came from the same society. Men were most often the killers. Women were the aggressors just four percent of the time.

“Most incidents of lethal aggression can aptly be called homicides, a few others feud, and only a minority warfare,” said the study.

Reasons for the killings varied, with 11.5 percent stating revenge as the motive, 9.5 percent saying it was over a particular woman, and 6.1 percent being cases when a husband killed his wife.

Twenty-two percent were linked to miscellaneous interpersonal disputes.

Less common motives included fights over resources such as a fruit tree (1.4 percent).

“In my view, the default for nomadic foragers is non warring,” Fry told Science.

Some anthropologists, however, said his method of winnowing down the societies for analysis and using only the oldest data on them could have skewed his results.

“The problem with the earliest accounts is they may be sketchy on all sorts of things,” Raymond Hames, professor of anthropology at the University of Nebraska, told Agence France Presse.

“In my mind, this is a very restrictive way of doing it, which I think accounts for his much lower estimates.”

Other researchers have found greater evidence of war-like behavior among hunter-gatherers.