Yangon, Myanmar – U Zaw Moe stands in a windowless white-walled prison cell on the outskirts of Yangon.

“This is similar to the one I was in,” he says, scoping the rectangular room, pointing to a few old blankets and a bucket in the corner that’s meant to be used as a toilet.

The cell, part of the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP) museum, aims to give visitors a sense of the conditions in which Zaw Moe and thousands of others in Myanmar were held for protesting against the country’s decades-long military rule.

But since his release in 2013, Zaw Moe, who now works with the AAPP, is not officially considered a former political prisoner. In fact, no one is because Myanmar’s government does not recognise the existence of political prisoners – past or present – even as it faces accusations of continuing to create them.

According to AAPP, which defines a political prisoner as “anyone who is arrested because of their perceived or active involvement or supporting role in political movements with peaceful or resistant means”, at least 35 political prisoners have been convicted since Aung San Suu Kyi‘s National League for Democracy (NLD) won landmark elections in 2015.

Another 56 await trial in prison, while 235 are on bail awaiting trial. That’s a 42 percent increase in the number of political prisoners the AAPP counted the year before.

|

| Wa Lone (centre) and his colleague Kyaw Soe Oo were found guilty in September of violating Myanmar’s State Secrets Act while working on a story about a massacre of Rohingya [File: Lynn Bo Bo/EPA-EFE] |

The AAPP says recent cases include Reuters journalists Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo, who were convicted of violating the colonial-era Official Secrets Act while investigating atrocities against the Rohingya and are now serving seven-year jail terms.

Others include anti-war protesters, farmers, former child soldiers and land-rights activists, according to the group.

The crackdown comes despite NLD promises to stop jailing people for criticising the government. U Tun Tun Hein, a spokesperson, vowed three years ago that the party would establish a definition for political prisoners once in power and “would not arrest anyone as political prisoners”.

A conveyor belt that will continue to send political prisoners to prison ad infinitum.

Phil Robertson, Human Rights Watch

And while Myanmar’s parliament has repealed or amended several laws that authorities once used to arrest and prosecute civilians for their political views, activists say freedom of expression is still under attack.

“By criminalising freedom of expression, association and peaceful public assembly, especially when criticism focuses on the government, the NLD has set up a conveyor belt that will continue to send political prisoners to prison ad infinitum,” said Phil Robertson, deputy director of Human Rights Watch’s Asia division.

“Only by reforming laws now used to prosecute expression and peaceful political activism will the government be able to turn that conveyor belt off and return to its early pledges to release all political prisoners.”

The dark ages

Under nearly 50 years of notorious military rule, there was no freedom of expression in Myanmar.

From crimson-robed monks to young students, those who dared to speak out against the government were beaten and arrested by police, and often sent to prison for years-long sentences. Aung San Suu Kyi, then portrayed as an icon of democracy, remained under house arrest for 15 years.

Amnesty International estimated Myanmar had more than 1,000 political prisoners at one time, calling it “one of the highest of such populations worldwide” but the military consistently denied their existence.

When the transitional government under retired general Thein Sein took power in 2012, more than 450 people walked free in a major prisoner amnesty. Activists’ hopes for an official recognition for political prisoners were raised further with the formation of a state-led committee “to scrutinise the remaining political prisoners serving their terms in prisons throughout the country so as to grant them liberty”.

But hopes were quickly dashed.

The Committee for Scrutinizing the Remaining Prisoners of Conscience was even formed, which was reconstitutioned in 2015, faced criticism for excluding the already existing AAPP, while rights groups and activists decried what they said was a failure to make any tangible progress for lasting political prisoner rights.

In 2017, a joint public statement released by 22 national and international groups said that it seemed the body was established “merely to deflect growing national and international criticism, rather than to resolve the issue of remaining political prisoners”.

Activists were disappointed that there was still no official recognition for political prisoners, and expected Aung San Suu Kyi’s government, itself made up of many former detainees, would do something to address the issue.

“We were hopeful that her administration would advance human rights when it came to power in 2016 with an overwhelming majority,” a spokesperson from Amnesty International, who declined to be identified for fear of reprisal, told Al Jazeera.

“Her government, in fact, was composed of many former political prisoners and had considerable authority to make real progress – especially to improve the climate for people to gather freely and peacefully speak their mind.”

|

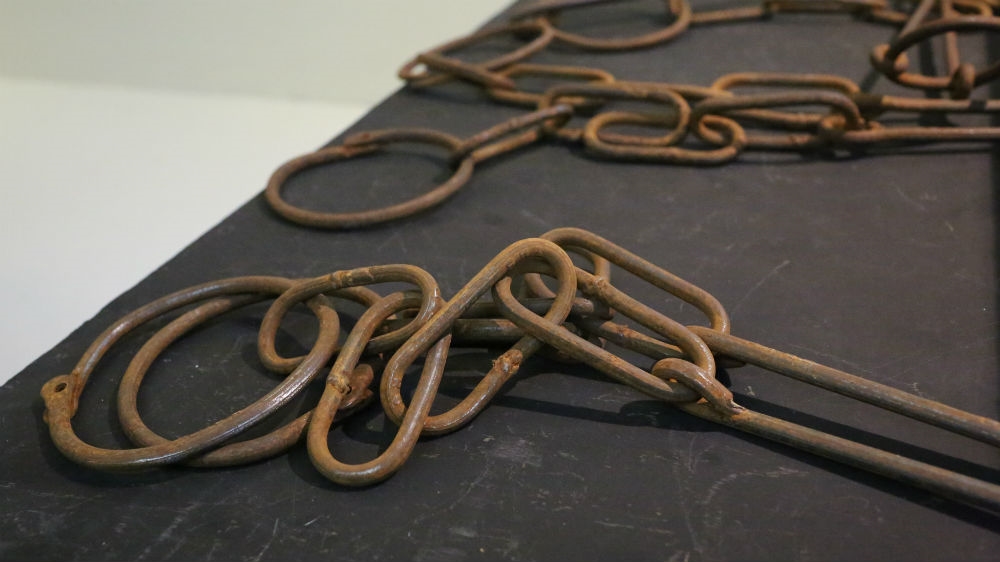

| Examples of shackles worn by political prisoners in Myanmar [Victoria Milko/Al Jazeera] |

A shackled democracy

Despite the democratic election, the military maintains considerable power.

The Ministry of Home Affairs, which is responsible for prisons, remains under the control of the armed forces.

In 2016, the government faced renewed calls to acknowledge and recognise the existence of former political prisoners. But Home Affairs deputy minister Major General Aung Soe claimed that it would be “unsuitable” for the terms to be defined in law, insisting that the constitution prevented any legal definition of the term.

“Under section 374, everyone has an equal right to protection of the law,” the military officer said in June 2016. “It would be against the constitution if we brought back the system of classifying prisoners.”

Parliamentarians were exasperated.

“The term ‘political prisoner’ is officially used, so why can’t parliament define it?” said former Yangon parliamentarian U Khine Maung Yi, referring to the usage of the term by various officials during speeches. “When a politician is arrested and charged with defamation for criticising the government, that’s a political offence. It’s time the government fixed this.”

But the refusal to establish recognition for political prisoners was not a complete surprise.

“Under the [military] regime, they had already said there are no political prisoners in Burma – so they have to maintain the stance of their previous superiors,” Zaw Moe said, using an alternative name for Myanmar. “If they officially defined political prisoners then they have to recognise all the prisoners they arrested, tortured and imprisoned in the past that they have already denied as being political prisoners.”

Al Jazeera was not able to get comment from the Ministry of Home Affairs.

|

| Images of past – and present – political prisoners in the Yangon museum of the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners. [Victoria Milko/Al Jazeera] |

Repression continues

The optimism that accompanied the NLD’s election victory has now largely evaporated.

“If the past three years are any indication, it is unlikely that this government will do anything to benefit prisoners of conscience,” Amnesty told Al Jazeera. “Repressive laws are still in place. In fact, the Myanmar authorities have been using them aggressively, and are still routinely sentencing journalists and peaceful activists on abusive charges.”

In the AAPP museum, Zaw Moe walks out of the jail cell and stands in front of another part of the exhibit – a wall of pictures that displays recently printed photographs of current political prisoners tacked on to a black foam board, with room for new photos that may need to be added.

While Zaw Moe says AAPP recognises the path to gaining official recognition for political prisoners is long, they will continue to work towards their goal.

“We are not talking about getting revenge,” said Zaw Moe.

“We are talking about preparing for the future and having accountability. We have to make sure this issue doesn’t have to be an issue in the future. If this happens again, all the effort we and members of the civilian government have put in will be lost.”