Fifty years ago, two African American track-and-field stars, having just been awarded their medals at the 1968 Olympic Summer Games and very aware that the eyes of the world were fastened to them, bowed their heads and raised black-gloved clenched fists under a Mexico City sky.

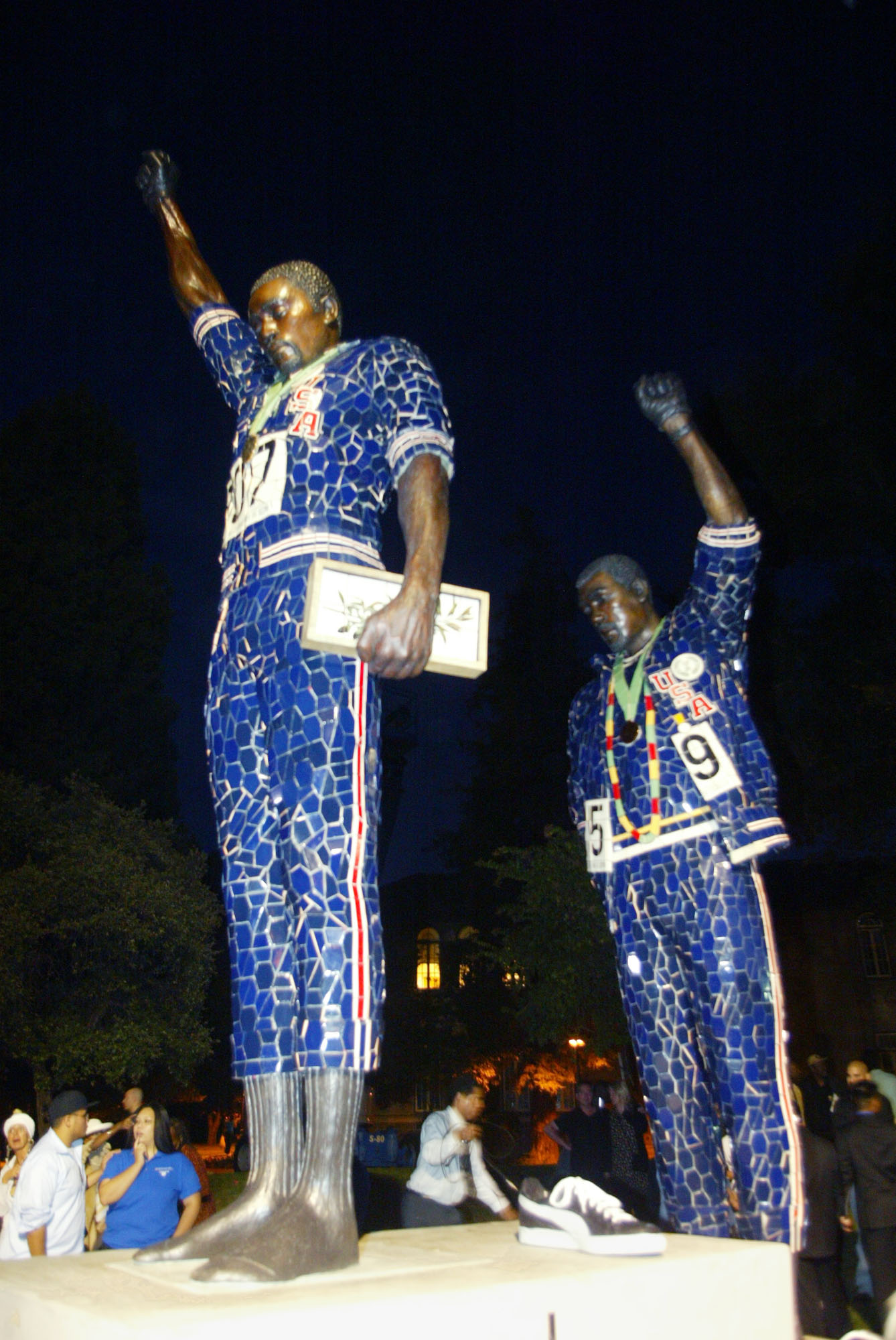

Those athletes – Tommie Smith and John Carlos – are beloved icons today. There have been statues erected of them, books written about them. The importance of what they did, and their bravery, is acknowledged in countless profiles, interviews and retrospectives each year. But today’s mainstream acceptance of their protest in 1968 is the inversion of the reality Smith and Carlos faced after taking their stand.

They had stripped the shoes off their feet, to shine a light on poverty. Carlos wore beads to honour the victims of lynching. Smith wore a black scarf to symbolise black pride. The silver-medal winner, Australian Peter Norman, supported the protest, donning a badge of a group Smith and Carlos were associated with, the Olympic Project for Human Rights. But these were all details for later. The crux of it all was what they did up on the podium.

As the Star-Spangled Banner played that night in 1968, they bowed their heads and raised their gloved fists, Smith’s right and Carlos’s left, in what is usually described as an unambiguous Black Power salute. It was a simple, nonviolent protest against racism, against exploitation, but it ignited an instantaneous firestorm of denunciation, beginning immediately with a largely unsympathetic crowd and the International Olympic Committee (IOC).

|

| Condemnation of Smith and Carlos’s protest was almost universal [File: Hulton Archive/Getty Images] |

The IOC was led at the time by Avery Brundage, infamous for his efforts to defeat and undermine any potential boycotts of the 1936 Olympics hosted by Nazi Germany, and who vehemently supported apartheid-era South Africa’s inclusion in the Olympic Games. Smith and Carlos were suspended from the US Olympic team and were instructed to leave the Olympic Village.

This nonviolent gesture of solidarity was to ravage their reputations for years to come. Condemnation was almost universal. Between them, Smith and Carlos received hundreds of death threats. They were called traitors. They were called “treasonable black rats”. It was commonly held that they had disgraced the Olympics and disgraced the American flag. Chicago columnist Brent Musburger went even further than most of their detractors and anointed Smith and Carlos, who had explicitly taken an anti-racist stance, “black-skinned stormtroopers”.

Dave Zirin, sports editor of The Nation and co-author (with Carlos) of The John Carlos Story: The Sports Moment That Changed the World, is unequivocal in his insistence that Smith and Carlos had almost non-existent institutional support.

Though a “young generation of activists was electrified” by the protest, this did not translate to the halls of power. “They were on an island,” Zirin told Al Jazeera.

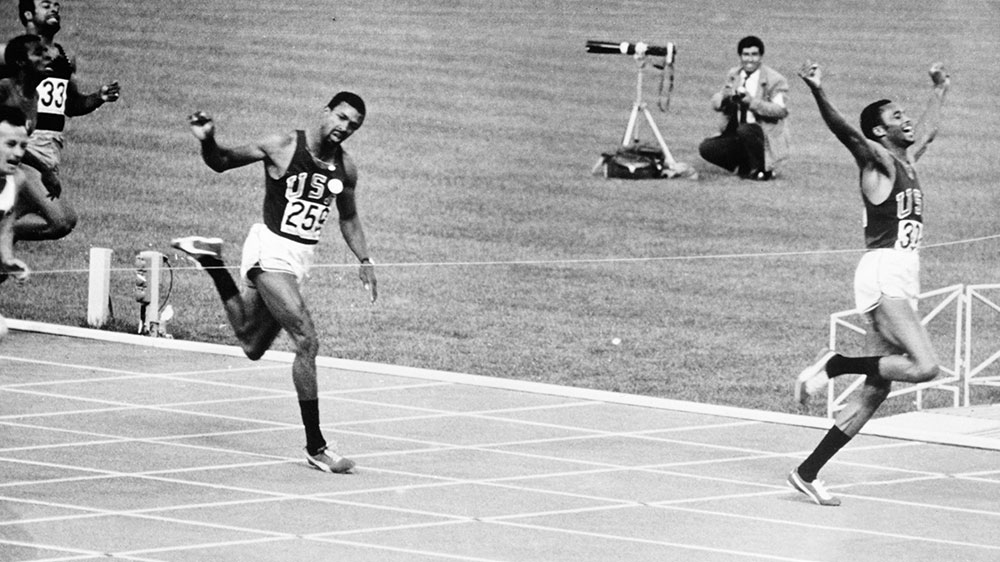

|

| Tommie Smith, right, of the USA wins the men’s 200 metres final at the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City. Bronze medalist John Carlos, also of the USA, is on the left [File: Douglas Miller/Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images] |

Support and admiration came decades later

Zirin believes it took until the 2000s – more than 30 years after that night in Mexico City – for their reputations to be satisfactorily rehabilitated.

This began in 2005, with Smith and Carlos’s alma mater San Jose State erecting statues to two as part of an entirely student-led endeavour and initially, without the support of the administration, Zirin said. Then in 2008, ESPN presented them with the Arthur Ashe Courage Award, complete with a video narrated by Tom Cruise.

The extent to which Smith and Carlos risked everything might not fully translate to a modern audience, however.

Colin Kaepernick, who has inspired and bedevilled large swaths of the US in fairly equal measure, has been given an award from Amnesty International. Nike has built a massive advertising campaign around the former NFL player, who in 2016 began kneeling during the national anthem at the start of each game to condemn police brutality against African Americans.

Although Kaepernick’s actions have drawn harsh words from President Donald Trump and other conservatives, Kaepernick’s actions have also inspired millions. Even some politicians have offered qualified support to the movement he helped inspire.

This sort of support system simply did not exist for Smith and Carlos, Zirin said, adding that social media have a role in this.

“Social media has played a part in amplifying the support, and people who are in politics feel they have to connect with that,” Zirin said.

He added, however, that the “Democratic Party was in a weird place in 1968” as pro-war Democrat Hubert Humphrey had emerged as the winner of his party’s presidential nomination against the backdrop of the Democratic National Convention riots in Chicago. He was to face Richard Nixon, a master of dog-whistle politics. There was no room in either party to endorse, let alone champion, the protests and sacrifices of Smith and Carlos. “They were very alone,” Zirin said.

‘Easier to praise people in hindsight’

Fifty years later, however, Carlos and Smith’s defining moment has largely been embraced by the mainstream in the US, not only as just, but also as heroic.

The contrast between the once-decried-but-now-exalted actions of mostly black athletes of the past and the mostly black athletes of today is stark. Muhammad Ali’s refusal to be drafted is the gold standard of this turnaround. Even less celebrated cases of political expression, like those of Craig Hodges or Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf, no longer inspire vitriol. More often, they evoke indifference from their one-time detractors, if they evoke anything at all.

The irony of reintegrating outspoken athletes of yesteryear like Smith and Carlos and Muhammad Ali into the fold of “respectability” while still cursing the name or burning the jersey of Kaepernick is not lost on observers of both eras.

“It’s always easier to praise people in hindsight,” Zirin said. “We saw that when Muhammad Ali died. And just a couple months later, Kaepernick did his protest. And the same writers who praised Ali denounced Kaepernick. They’re just following the fashion.”

‘We weren’t wrong. We were ahead of our time’

For their part, Smith and Carlos fully embrace this new wave of athlete activism.

One lesson that can be gleaned from the pair to modern socially conscious athletes is that progress may seem slow, and public opinion slower, but the world tends to catch up. This may seem a frustrating blueprint for success, one predicated on just waiting out regressive ideas and hoping for the best.

But if Smith and Carlos proved anything, it’s that the protests of today aren’t just for today. They belong to the next generation, and the next. Their defiance and their abdication of privileges of young world-class athletes affect future protests on every field, in every stadium and in every arena.

John Carlos talks protest in sports, and his iconic rebellion at the 1968 Olympics. pic.twitter.com/N8JTb3hEze https://t.co/5kDmaG4l7M

— AJ+ (@ajplus) October 16, 2018

Kaepernick, Megan Rapinoe, LeBron James and the WNBA, which is considered by many as one of the most progressive and socially conscious professional sports leagues in the US, are among the natural heirs to the raised fist in a black glove, to the black scarf, to the beads honouring the victims of lynching.

And in an era in which the president of the United States has all but declared war on athletes who protest, many would argue the need for the athletes willing to use their platforms to advance social change is more imperative than ever.

Even as the new generation steps up to their own podiums, there is no regret about the decision Smith and Carlos jointly made 50 years ago on Tuesday. As Smith said in 2016: “We were not wrong. We were only ahead of our time.”