Maiduguri, Nigeria – When a Boko Haram fighter called in during Hauwa Tiramisu’s late-evening radio programme at Dandal Kura International last summer, the presenter froze.

“He said what we are doing is bad and forbidden,” she said. “[He said] we are working with the government and they’d come for us.

“I was shocked. I was really shocked. I was afraid that night.”

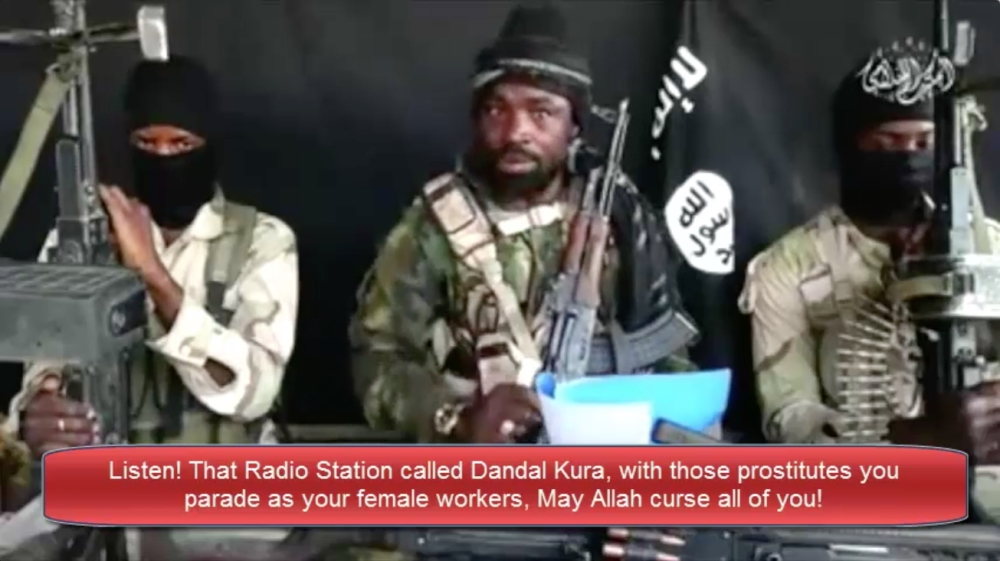

Three months earlier, Abubakar Shekau, the leader of Boko Haram, released a video describing the radio station’s female employees as prostitutes.

“Listen! That radio station called Dandal Kura, with those prostitutes you parade as your female workers. May Allah curse all of you,” Shekau says, in the local Kanuri language.

|

| A screenshot from the video Boko Haram released, in which the group threatened attacks on the radio station [Courtesy: Dandal Kura] |

Over the past seven years, Boko Haram has been attempting to install a caliphate in northeast Nigeria.

Since 2009, at least 20,000 people have been killed because of violence. More than five million people do not have regular access to food and nearly two million people have been displaced.

Launched in the northwestern state of Kano in 2015, Dandal Kura was established by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) with Nigerian journalist and manager Faruk Dalhatu and David Smith, the station’s Canadian project lead.

In 2016, the channel – which is editorially independent – moved to Maiduguri, the Borno State capital, as relative peace returned to the city.

The station broadcasts information about the government’s efforts against Boko Haram and informs listeners of fighters’ activities and planned attacks.

“People will call us during our live programmes to inform us about an attack in a town, this helps the neighbouring town to be vigilant,” says Bello Sani, head of operations at the station.

There are news bulletins, regular updates from the station’s 30 correspondents, and an array of feature programmes on “deradicalisation”, education and entrepreneurship.

|

| Presenter Yabuwa Ismail reads the news at the radio station [Festus Iyorah/Al Jazeera] |

“Dandal kura” translates as a large meeting place.

The station can be accessed by more than 10 million Kanuri speakers across Nigerian states and neighbouring Chad, Cameroon, Niger and Sudan.

“Dandal Kura was established to roll back the narratives of Boko Haram,” says Dalhatu, the manager, “and to produce quality content that will help to improve communities.”

The station chose the local Kanuri language because “if we have to counter [Boko Haram leader Shekau’s] ideology, we have to do that in his own language,” said Sani, the head of operations.

At the peak of Boko Haram’s campaign of violence, the radio station featured psychologists, counsellors and Muslim leaders to demystify the group’s ideology.

They also informed the audience of security measures to take as attacks raged across villages and towns in the northeast.

Keen listeners such as 54-year-old Bukar Muhammed learned how to avoid traffic jams, insecure areas and crowded hubs – all prime targets for suicide bombers.

“What also interests me about the station is most of the programmes are done in Kanuri. And I have an interest in any programme that is aired in my own language,” Bukar said.

The threats mean our messages are reaching the uppermost echelons of Boko Haram’s leadership.

Faruk Dalhatu, jouranlist and Dandal Kura manager

The station is tucked away in an apartment in an old and safe government residential area, guarded by security agents with AK-47 guns at the entrance.

There is nothing to identify the radio station.

“This is deliberate,” said Sani. “Initially, we had a banner and a signpost. But we removed them because there were threats.”

As well as the Boko Haram video, the radio station received a series of phone calls promising attacks unless it stopped broadcasting.

As a result, security was beefed up with new doors installed in the newsroom and studio.

Interns, casual workers and visitors can only enter with senior staff members.

While troubling, Dalhatu said the threats suggest the station is doing something right.

“[The threats] mean our messages are reaching the uppermost echelons of [Boko Haram’s] leadership,” he said.

Musa Liman, a senior lecturer in mass communication at the University of Maiduguri, said the station has a positive effect.

“Its significance was felt because people got to know about Boko Haram’s strategy and [some of] those who were about to be recruited decided not to get entangled,” she said.

Looking ahead, Dandal Kura plans to tackle another scourge which acts as a motivating factor for recruits to armed groups – unemployment.

“We want this station to be sustained because there’s none like it and it is serving a useful purpose,” says Dalhatu.

Back at the station, an atmosphere of fear still hangs in the studios.

Sani is yet to relocate his family to Maiduguri. He visits them often in Kano, which is about 600km away.

“I have never felt confident to bring them here. When I know my family is safe, it takes the pressure off,” he says. “But I am not safe.”