When Pope John Paul became the first pontiff to visit Ireland in 1979, almost half the island’s population turned out to see him as he toured the country.

His Sunday mass in Dublin’s Phoenix Park became the largest gathering Ireland had ever seen, with 1.2 million attendees.

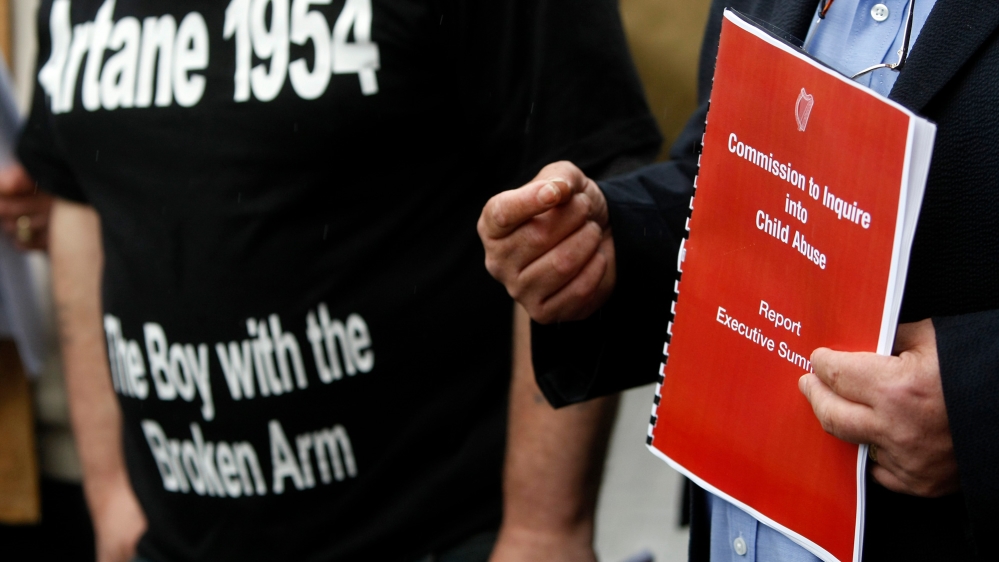

It was an Ireland where condoms, abortion and homosexuality were banned by law, and whether unknown or not addressed, thousands of children were raped and abused by members of the Catholic clergy.

On Saturday, Pope Francis is expected to begin a 36-hour trip to Ireland, to attend the World Meeting of Families, a gathering of the Roman Catholic Church held every three years.

A crowd of half a million is expected in Dublin, but attention is expected to focus on claims of child sex abuse.

The Vatican said on Tuesday that Pope Francis will meet survivors, following demands from campaigners for action, accountability and justice for those who were affected.

“Ninety-four percent of accused walked free, and that’s of the abusers. This is the perpetrator population, we’re not even getting near the population of those … who concealed or colluded.

Mark Vincent Healy, survivor and campaigner

The visit comes little more than a week after a grand jury report released in Pennsylvania revealed the covering up of more than 1,000 cases of children abused by over 300 priests.

The report’s criticisms of Cardinal Donald Wuerl led to his withdrawal from a scheduled appearance at this weekend’s event in Dublin, where he was to deliver the keynote address, “The Welfare of the Family is Decisive for the Future of the World”.

The Pennsylvania news has brought further scrutiny upon Pope Francis, who is widely seen to be weak on an issue that has caused catastrophic damage to the Church’s reputation worldwide.

Listing the accused

On Monday, US-based group BishopAccountability.org launched the first open database of Irish clergy accused of child sexual abuse. The website already hosts similar information on those publicly accused of abuse in the US, Chile and Argentina.

The Irish database lists dozens of clergy members who have been convicted, or whose abuses have been alleged and documented in the media or by state-led inquiries.

It includes figures such as Brendan Smyth, a priest from Belfast who sexually abused or assaulted at least 143 children over a period of 40 years.

Smyth was shuffled between parishes in Ireland and the US, his order repeatedly failing to disclose his history to local bishops, before eventually being sentenced to prison in 1994, where he died three years later.

|

| John Kelly, right, was abused while in Daingean Industrial School between 1965 and 1967 [File: Cathal McNaughton/Reuters] |

The group said in a statement that it hopes “this Irish database will encourage an open debate about how societies balance an accused person’s privacy rights against a child’s right to be safe and the public’s right to know”.

Codirector of BishopAccountability.org Anne Barrett Doyle added: “It’s a very unsatisfactory list because we know from the Irish Church’s own safeguarding operation has counted more than 1,300 accused clergy since 1975.

“We have a paltry 70 or 80 on our list. This represents an accountability gap, not just a gap in unnamed perpetrators … I think it’s why the abuse crisis is very much an open wound in Ireland.”

Another name on the list is Henry Maloney, who was convicted in 2009. He abused boys at a Dublin secondary school between 1969 and 1973, after which he was transferred to another school in Bo, Sierra Leone where he continued to molest students.

Life after abuse

Mark Vincent Healy, who was among those abused by Maloney, now campaigns for justice.

Before the pope’s visit, he gathered research from more than 140 reports into religious orders and dioceses by the Irish Catholic Church’s National Board for Safeguarding Children (NBSCCCI).

According to Healy, of the 3,425 allegations raised in these reports against 1,348 people, only 82 were convicted.

“Ninety-four percent of accused walked free, and that’s of the abusers,” he told Al Jazeera. “This is the perpetrator population, we’re not even getting near the population of those … who concealed or colluded.”

|

| A demonstrator holds a banner during a protest against the visit of Pope Benedict XVI in London on September 18, 2010 [Stefan Wermuth/Reuters] |

But there are limits to what can be achieved through the courts, Healy says.

Research has shown that survivors of child sexual abuse in Ireland face lifelong consequences.

They are more likely to be unemployed, earn less and die by suicide than the general population. Male survivors are also more likely to spend time in prison.

“We do need justice, it’s absolutely fundamental, but I feel the discussion doesn’t permit talking about the dysfunctional life that is the consequence of this abuse, and how can we better serve that community,” says Healy.

“How do we reach out to them and offer them the sort of support for issues which they are wholly innocent of having happened to them?”

Pope Francis: We did not act in a timely manner

In a 2,000-word letter published this week and addressed to the world’s Catholics, Pope Francis acknowledged the Church’s history of abuse and cover-ups, including the cases in Pensylvania.

“We did not act in a timely manner, realising the magnitude and the gravity of the damage done to so many lives. We showed no care for the little ones; we abandoned them,” he wrote.

But critics hit back at the lack of concrete proposals.

Former head of the NBSCCCI Ian Elliot told the Irish Times that the pope’s record has been “a dismal failure” and that he should arrive in Ireland with “a mindset that it’s not good enough to simply apologise”.

|

| Candles with a picture of Pope Francis on sale at a stall in Dublin [Clodagh Kilcoyne/Reuters] |

Mary McAleese, the former Irish president, dismissed the World Meeting of Families as “essentially a right-wing rally”, while Taoiseach Leo Varadkar suggested the Church adopt a policy of mandatory reporting, which has been in place in Ireland since last year.

In his Sunday sermon, Archbishop of Dublin Diarmiud Martin said Pope Francis should “speak frankly about our past but also our future.” But he said the pontiff would not be able to provide all the answers that people ask.

For Barrett Doyle, the public database is a small step in confronting a history of neglect towards Ireland’s most vulnerable.

“We are being inundated with emails from Irish people who have seen the list and are asking us to add abusers names to it,” she says. “We obviously struck a nerve. There is a tremendous need for this.”