Tehran, Iran – Reza, 27, wanted to work in a stock exchange firm, or in an insurance company in the Iranian capital. He had high expectations. Years before, he topped Iran’s cut-throat university entrance exams, Konkour, and is currently working on his master’s degree in economics at one of the country’s best universities.

But for years, he hasn’t been able to find work in a job market with recurring double-digit unemployment rates. He ended up becoming the driver of a motorbike taxi, a speedy and cheap mode of transportation in Tehran’s traffic-clogged streets.

Then in 2017, Reza sensed a new opportunity to earn some extra cash as the country’s currency, the rial, started to fall.

Reza, who requested his last name not be used, became a currency trader in Tehran’s black market.

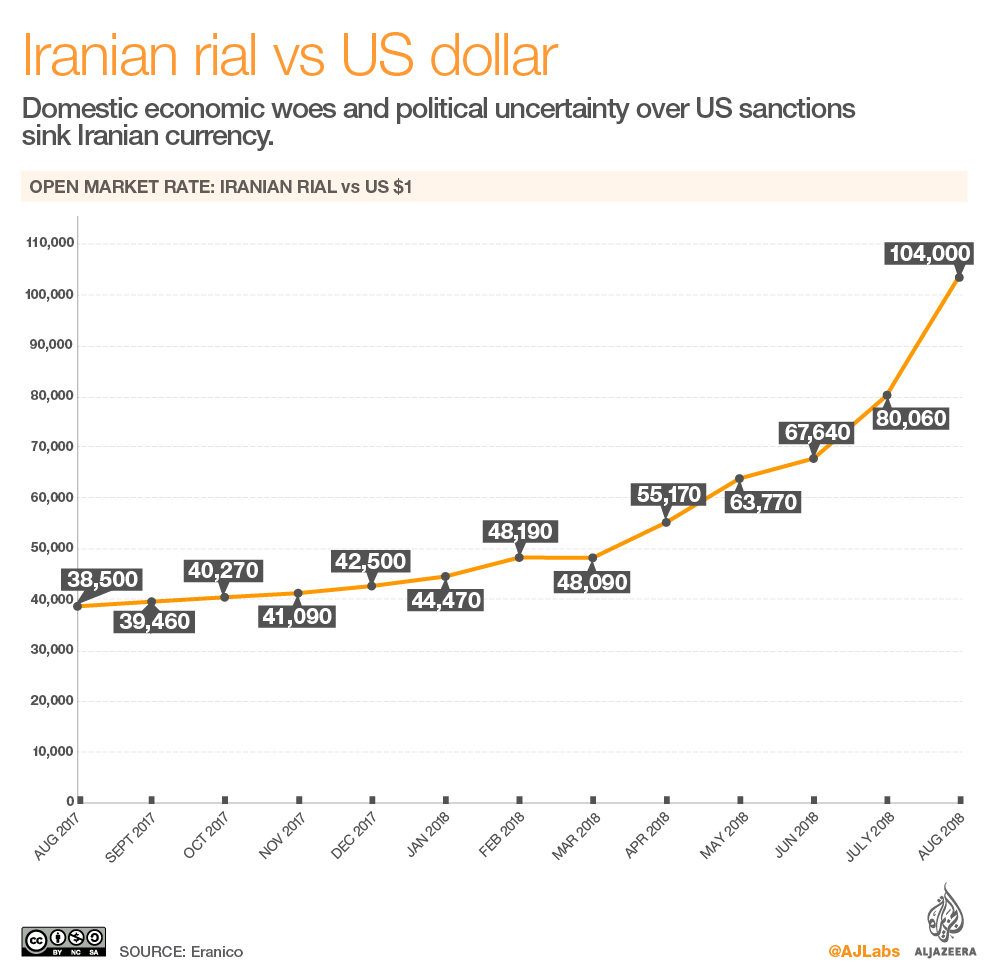

He withdrew his rial deposits, worth an estimated $26,000 at the time, and put it in his new enterprise. Based on an August 2017 exchange rate, $1 was equivalent to about 38,400 rials in the open market.

Despite the risks, the decision made sense to him, Reza told Al Jazeera. He needed to protect his savings. Keeping local currency in the bank, and leaving it at the mercy of monetary fluctuations, would have left him $16,400 poorer by now, based on the August 13, 2018 exchange rate of $1 to 104,000 rials.

Since last year, internal domestic pressures on the Iranian economy, and the uncertainty over US President Donald Trump’s threat to withdraw from the 2015 nuclear deal, resulted in the rial losing more than half its value.

The drop was particularly steep in the days leading to the reimposition of the first round of US sanctions on August 7. Recent burst of protests across the country also added to the anxiety.

As the currency continued to fall, frantic Iranians seeking to convert their savings into dollars were chasing after Reza and his band of traders. For Reza and his cohorts, the trick to make a profit was simple: Buy dollars and euro low, sell high.

“Fluctuations in the market works in favour of the middlemen,” Reza said.

And because demand for dollars remains high, they are able to dictate the price, sending the rial further into a tailspin.

|

| Infographic by Alia Chughtai |

Trading at Ferdowsi

Tehran’s Ferdowsi Square is famous for two things: leather bags and currency traders. That is where Reza and his pals hang out, under the gaze of the marble statue of Ferdowsi, the Persian poet and author of Iran’s national epic, Shahnameh.

When not in class for his master’s degree, Reza wakes up at 8am to be at his usual spot at the square at 10am, hustling as late as 8pm.

Counting the cost: $1=About 107,100 Iranian rial – Currency rate in the open market as of Aug. 14, 2018. #Tehran #Iran #IranUnderSanctions #IranDeal pic.twitter.com/rHrP0PvzjK

— Ted Regencia ??? (@tedregencia) August 14, 2018

With a quick glance at the crowd, Reza can spot a foreign face looking to exchange money. After a brief chase, or a low-key call out, a transaction can be had in a couple of minutes.

“Being a middleman is full of stress, but it is sweet especially when you make good money,” said Reza, casually dressed in a plaid shirt and khakis, and growing stubble that masks his younger face.

Reza said he is not making money just for himself, but also for his family. Although he is single, he supports his elderly parents, two sisters and two brothers, one of whom also works as a currency trader.

While the currency market may be good for Reza’s bottom line, he said overall Trump’s rhetoric against Iran is “too bad for our economy”.

Police crackdown

Trading in the currency black market is considered smuggling in Iran, making Reza and other money market dealers targets in a police crackdown.

|

| Iranians complain Trump’s rhetoric against Iran has dampened the country’s economic prosperity [Ted Regencia/Al Jazeera] |

In February, as the rial showed its first signs of wobbling this year, mass arrests were carried out at Ferdowsi Square and nearby streets, and the government reportedly froze rial deposits worth billions of dollars in an attempt to control the rial’s slide.

In July, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani fired central bank governor Valiolah Seif as part of the country’s monetary policy shake-up. Seif’s deputy, Ahmad Araghchi, who oversees the country’s foreign exchange, was also replaced and later arrested, according to reports.

There has been speculation the currency could face more pressure when the second round of US sanctions will be reimposed in November, hitting Iran’s energy exports – a major source of its finances.

But economic journalist Maziar Motamedi told Al Jazeera he does not expect the devaluation of the rial to be as painful to Iran as the US government and Trump had pledged, because of new policies being implemented by Tehran.

Rouhani’s government “seemingly wants to promote an open market”, he said.

“If it manages to fully implement its announced policies and support a market free of government meddling, the consensus among pundits is that the rial will gain.”

The central bank also continues to maintain a lower preferential rate of $1 to 42,000 rial. However, that is only offered to energy-related business activities and traders of essential goods. But that has not been free from abuse by profiteers.

As for Reza, he continues to place his bet against the rial despite government warnings that currency speculators will be prosecuted. In the current economic crunch, there is not much of an alternative for him to earn a living anyway.

On the morning of Reza’s interview with Al Jazeera, police came to Ferdowsi Square to make arrests.

“If they catch you, they will fine you three times worth the amount of money you have,” Reza said.

And what if police target Reza and his trader friends?

“We will just run like cats.”

Infographic design by Alia Chughtai

|

The future of Iran nuclear deal after new US sanctions |